A Hierarchy First Approach to Note Taking

Ten years ago I wrote a note.

That led to another, and then another, and soon enough, I had a few thousand of them and an increasingly unhappy dropbox client that refused to sync it all.

The reason for all these notes is because of technology.

I worked at AWS and tried to keep on top of cloud stuff. I programmed in three different languages and kept notes to help me context switch between different programming languages. I also did full-stack development on the side and that, well, it required referencing everything.

My primary use for notes is as a cache. Think Redis, but for humans.

If I spent more than 5 minutes figuring something out, those are five minutes I never want to spend again figuring out the same problem.

But this is difficult to do in practice.

Sometimes you run into a thing that only pops up on some specific version of a cli command on an outdated bash shell on a specific Linux distro. How do you document this sort of thing when you might encounter a dozen of them a day?

My solution is something I call hierarchical note taking. It's a system I've developed over the past ten years that has allowed me to amass a corpus of +10k notes.

This system has some awesome properties that I haven't been able to replicate with anything else:

- it lets me find any specific note within seconds even with thousands of existing notes

- it helps me build a comprehensive mental model around a domain through the act of organizing my notes

- it can be used on any note-taking tool that supports markdown notes

- it's compatible with existing note-taking methodologies like PARA

The rest of this post will describe the journey I took to arrive at hierarchical note-taking and the problems that they help me solve.

The Problem with CLIs

I spend a lot of time in the command line in Unix-like systems. If you do as well, you might be familiar with the following comic.

Comic from XKCD

I've probably used tar a few thousand times in my life but still can't tell you what the arguments mean (it's mostly muscle memory at this point). Unix tools do one thing and one thing well, and on most days, that one thing is making you reach for a man page.

This is because every command has many dozen options, many of which are invoked with obscure single character letters in a specific order for specific inputs (I'm looking at you rsync).

Growing tired of reading man pages and stack overflow threads, I wanted a way to capture and reference commands that I've run in the past. And so I started taking notes.

I created a folder called notes. I created a note called tar.md.

Note that my tar.md note doesn't have every option or use case involving tar. Instead, it's only the options that I find most useful and use cases that I've had to do. This tends to be my approach to note-taking - I like to capture the bare minimum information I need so that the future me can get value out of the note.

What started as a single markdown file quickly spawned a few hundred more. It was exhilarating - instead of turning to google every time I ran into a dusty corner of Linux, I could just reference my notes. 95% of the time, there would be a nicely summarized note waiting for me :)

The Problem with Languages

While the above approach worked for cli commands, things got more complicated as I needed notes on additional domains. Most commonly with my work, it was programming languages.

Take python as an example. Python is both a programming language as well as a cli command. Without changing the name of one of the notes or introducing folders, there would be no way to create notes on both.

But I didn't want folders. Folders were messy and besides, weren't supported in notational velocity, my primary note-taking tool at the time. So instead of folders, I decided to create a hierarchy using the . symbol as my delimiter.

Now I could represent the language and the cli as two different . delimited hierarchies.

cli.python.md

lang.python.md

Though on the surface, this seems like a simple change and not all that different from a traditional folder hierarchy, I found that it equal to the difference between using a commodore 64 and the latest (non-butterfly keyboard) Macbook.

For starters, files now had the ability to both contain data and have children. They could act as both files and folders.

And whereas folders were traditionally used to organize information, there was no straightforward way to use a folder hierarchy to quickly find information. Having the hierarchy in the filename made it easy to find information using the hierarchy.

Finding the Truth

There's the joke in computer science that there are only 3 meaningful quantities in the field: 0, 1 or infinite. If you can create a thing more than once, there is nothing in theory that should stop you from creating an infinite amount of said thing.

Once I realized I had a system of making two-level hierarchies, I realized I didn't need to stop there. This soon led to deeper hierarchies like the one below.

.

└── lang

└── python

├── data

│ ├── boolean

│ ├── array

│ ├── string

│ └── flow

├── flow

│ ├── for

│ ├── while

│ └── if

└── operator

├── comment

├── compare

├── scope

├── inspect

├── format

├── iterate

└── destructure

The above hierarchy was stored as simple plain text files inside my notes folder.

lang.python.data.boolean.md

lang.python.data.array.md

lang.python.data.string.md

lang.python.flow.md

lang.python.flow.for.md

lang.python.flow.while.md

lang.python.flow.if.md

lang.python.operator.md

lang.python.operator.comment.md

lang.python.operator.compare.md

lang.python.operator.scope.md

lang.python.operator.inspect.md

lang.python.operator.format.md

lang.python.operator.iterate.md

lang.python.operator.destructure.md

With this hierarchy, I could quickly reference anything I needed from a programming language.

Looking up different data structures in python

Once I built out my hierarchy on python, I found that I could also apply it to any other language. This made context switching between languages much easier.

As an example, I can never remember what counts as truthy in dynamic languages. But now I don't have to.

Finding the truth

The cool thing about this approach is that the implementation details of any particular language became less important as I build out my hierarchies. Instead of thinking in terms of "how well do I understand python", I think in terms of how well I understand programming languages.

Externalizing Mental Models

As I started building hierarchies across more and more domains, I found that it became useful to document what they were. I called these externalized hierarchies schemas. They were a table of contents for a particular hierarchy. I started adding a special schema file directly underneath the root of each hierarchy.

lang.schema.md

cli.schema.md

aws.schema.md

...

Inside each schema note, I would have something like the following

- lang (namespace) # indicates that there are any number of languages underneath here

- data: data structures

- flow: control flow

- oo: object-oriented programming

- ...

I would use schemas as a common source of truth when building out a hierarchy and use them to make sure that each hierarchy was internally consistent. As I began to use this system day by day, I realized that I had stumbled upon a radically more effective way of learning.

Hierarchical Notes

By associating every note I took to a hierarchy, I found that looking up information no longer felt like an tax on my time, but instead, a path to self augmentation.

Whereas before I would look up a thing only to forget it a few weeks later, I could now quickly incorporate it into my notes and know with certainty that I will be able to reference this again at a later date.

Better yet, when I found something that didn't fit any of my existing hierarchies, I could use it as a chance to update my schemas on said hierarchies. This would slowly expand my conceptual understanding of the entire domain.

A concrete example: earlier this year, I ended up making use of the null coalescing operator in javascript. This is a convenient way of assigning values when dealing with null

In the following example, a will be assigned the value of b if the value of b is not null or undefined, otherwise, it will be assigned 3.

const a = b ?? 3;

After learning about it, I added it to my language schema under operators.

- lang (namespace)

- {specific language}

- operator (alias: op)

- add

- subtract

- ...

- null # null coalescing operator

Not only did this expand my vocabulary of language operators, but it also let me note down how the equivalent functionality can be expressed in languages that did not natively support it.

other = s or "some default value"

Python example of "null coalescing"

What is nice about this approach is that I have completely divorced the concept of "null coalescing" with the implementation detail of any particular language. The next time I'm using python and want to do null coalescing, I can simply look up python.op.null and be reminded of the implementation.

There are dozens of main stream programming languages. There are hundreds of additional domain-specific languages. In a prior life, there would have been no way for me to know even a tiny fraction of them. But a hierarchical first approach to note-taking changes the game - instead of having to know the details of every language, I can collapse it all down to my one language schema. This schema can capture the points of interest of every language and in this way, I can claim to know something of all programming languages.

The Present Day

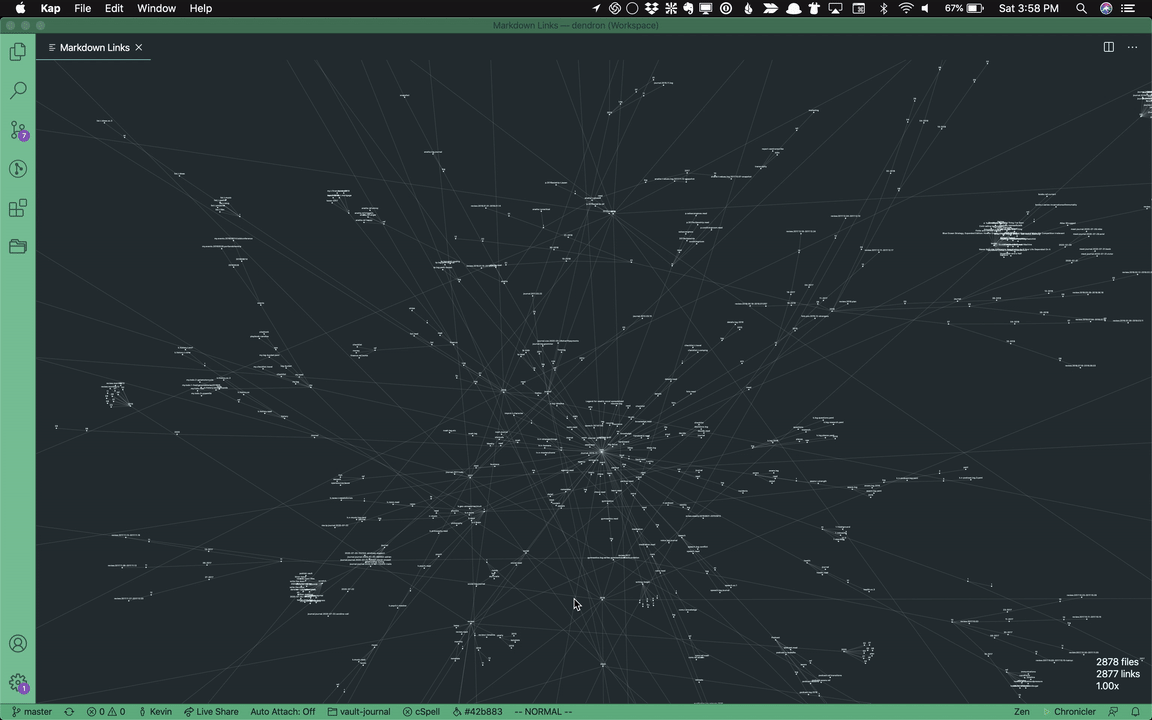

Today, my knowledge base encompasses over a dozen different hierarchies that span 10K+ notes. I've expanded my use cases of note-taking beyond caching to also include journaling, task management, creating writing, keeping track of interactions, and lots more.

My journal notes for the last five years.

I've also expanded my schemas and have migrated from free form bullets to a structured YAML syntax.

version: 1

schemas:

- id: l

title: language

desc: programming language

parent: root

data:

namespace: true

children:

- operator

- d

- flow

- lib

- dev

- t

- files

- oo

- func

- types

# --- operator

- id: operator

children:

- comment

- create

- compare

- equal

- scope

- inspect

- format

- iterate

- destructure

...

My programming language schema

Hierarchical note-taking has been the most valuable investment I've made in the last decade. My notes, in turn, have helped me learn, grow, and be better in all areas of my life.

One thing that has puzzled me over the years is why no one else was doing this. Most of my peers did no kind of note-taking, and the ones that did were constantly switching between different tools and methodologies to try to manage it all.

A little over a year ago, I left my job at Amazon to work on a note-taking tool built around the concept of hierarchical notes. Hierarchical note-taking is a system that I spent the greater part of a decade iterating on, and it is now a system that I want to share with the world.

Dendron

About a month ago, I launched the preview for Dendron. Dendron is the first-ever note-taking tool built from the ground up to support hierarchical note-taking. Dendron is open source, local first, Markdown-based, and runs as a collection of extension on top of VSCode.

Dendron lives inside VSCode because I wanted to move fast and focus on the truly novel parts of hierarchical notes without also building all the scaffolding that comes from creating an editor. Living inside VSCode means that users also have access to the thousands of existing extensions that provide everything from vim keybindings to realtime collaboration editing.

Over 50 years ago, Vannevar Bush, an early visionary in information science, said something about the field that strikes a deep chord with me.

"We are overwhelmed with information and we don't have the tools to properly index and filter through it. [The development of these tools, which] will give society access to and command over the inherited knowledge of the ages [should] be the first objective of our scientist" - Vannevar Bush, 1945

50 years later, this statement is just as true. The tools haven't changed but the information has only become more overwhelming.

Dendron is my attempt at building a tool that will give humans access to and command over the inherited knowledge of the ages.

If this mission statement resonates, I hope you join me on the journey! There are many ways to be involved:

- you can download dendron and start/continue a note-taking habit

- you can take a look at our open road map and leave comments and thoughts

- you can join our discord community of fellow note-takers

- you can follow us on twitter at @dendronhq

- you can star and watch us on github

Whatever path you take, safe travels and hope you take note of the journey!

Staying Updated

If you liked this article and would like to get more like it, feel free to subscribe to my mailing list. I publish around once a week and share my thoughts on knowledge management and workflows that I find effective.

Tags

Backlinks