Benchmarking Lambda's Idle Timeout Before A Cold Start

History of Compute

In the not so distant past, businesses that wanted to build internet services needed to provision their own hardware. That meant buying a rack and a bunch of servers and stashing them in a cool part of the building and hope that no one would trip over the wires.

As businesses grew, so did their IT infrastructure which meant that they sometimes had to expand into data centers to handle all that new traffic. Besides costing an obscene amount of money, this also involved much complexity, especially as traffic spiked, machines failed and disks died.

Then came the advent of cloud computing which promised to free businesses from all that complexity for a less obscene amount of money. Instead of ordering hardware ahead of time, a server of your choice was just an API call away. This meant that companies could pay only for the traffic they have today but also have the capacity to handle spikes and growth.

Cloud computing drastically slashed the capital and hardware necessary for businesses to scale up their IT. But under the hood, it was still running workloads on VMs in the same way that people have been doing since dot com. But all this changed in a big way November of 2014.

AWS Lambda

AWS introduced Lambda during re:invent of 2014 and presented it as a new paradigm for thinking about code. Instead of worrying about servers, upload the application code and lambda would take care of the rest.

Lambda promised instant deployments and infinite scale with the benefit of costing nothing when it wasn't invoked. But as with any technology, there are tradeoffs for having nice things and with Lambda, one of those tradeoffs is cold starts.

Cold Starts

Lambda executes code in containers. During the first invocation of your function, Lambda will instantiate the container containing your application code. This initial initialization cost is known as a cold start.

The penalty of a cold start varies by language, framework, memory allocation and whether you're running your Lambda inside a VPC (just don't). Typically, it can be anywhere from ~200ms (python) to over 5s (C#). For a more detailed analysis on the breakdown, you can read the following post.

Subsequent calls to Lambda will reuse the initial container. Lambda will keep the container hot as long as it continues to be invoked within an idle timeout interval. The value of this idle timeout is not published by AWS and the subject of this post.

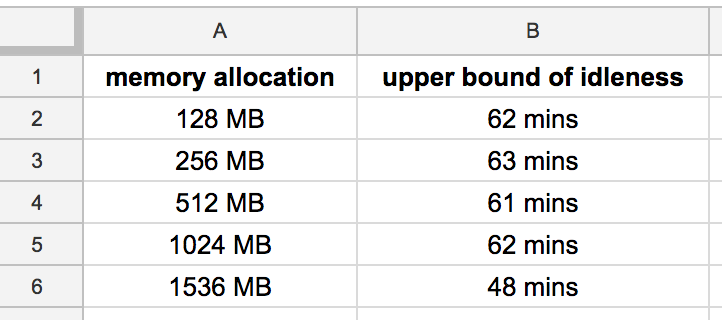

Before I begin, I have to mention that I'm not the first person to write about this topic. I personally like the analysis done by AWS Hero Yan Cui. By executing Lambdas of various memory sizes with monotonically increasing idle wait times between each invocation, Cui was able to derive an upper bound for idle timeout of various Lambda sizes. An image of his results is posted below.

Based on the above numbers, it seemed that Lambda containers were able to idle for as much as an hour before being reaped. Whether Lambda's would actually idle for that long seemed to depend on Lambda size and VM utilization.

Cui published his post in 2017 and Lambda has made extensive changes to the platform in that time, including increasing the memory limit of Lambda to 3GB. I was curious to see how idle timeout changed in the interim and run the test for the bigger Lambda memory sizes.

For the test, I re-used Yan Cui's code and setup - this involves creating a series of lambdas using the serverless framework and orchestrating the tests using step functions. We start off with an idle timeout hard coded at 10min and use step functions to continuously invoke the lambda function to see if we get a cold start. If not, we increase the timeout, wait and try again. We repeat this process until we get 10 cold starts and use the maximum timeout to determine an upper bound on the idle timeout.

The following test was conducted in us-west-2 at 2019-01-29

Results (us-west-2)

And now for the results. Drum roll... 🥁🥁🥁

So this turned out not be the most exciting graph in the world and also different from what I was expecting. 26min was not just the max idle timeout but the idle timeout we got in every execution of Lambda across all memory sizes.

To read the above table, know that the first column is the Lambda memory size and the other columns show the statistical properties of the idle timeout in minutes.

The idle timeout of 26min is actually half the max idle timeout from when Cui did his benchmark in 2017. This is also 5x more than what tools like the serverless-plugin-warmup will ping your lambda at (default is set to 5min). Something to note is that these results only show the upper bound of the idle timeout and it could very well be the case that the lambdas did timeout after 5minutes though the consistency of the results would suggest otherwise.

But Wait...

At this point, I was ready to make dinner and call it a day but there was one more thing I wanted to do before wrapping up the experiment. Something to always consider when doing a benchmark on AWS is that it is always region dependent. Each AWS region is designed to be completely isolated from other Amazon regions - this means physical proximity, hardware, power supply, etc. The instance type availability differs from region to region and so can the code that is deployed within each region. us-east-1 is AWS's oldest region and has the widest possible skew in terms of instance availability and workloads. I wanted to find out if the observed Lambda idle timeouts were also consistent here so I repeated the above experiment in us-east-1.

The following test was conducted in us-east-1 at 2019-02-01

Results (us-east-1)

So this is a more interesting graph. Note that there is a general trend of the idle timeout decreasing with higher memory allocations.

Some immediate observations:

- 2624MB lambda shows the same behavior as us-west-2 lambda, having a consistent idle timeout of 26min

- all other lambdas have higher idle timeouts, all the way up to 65min

- initial idle timeout still starts at 26min with two exceptions, 31min for 256MB and 22min for 1856MB

- 1024MB lambda is only Lambda under 1536MB to have under 60min of idle timeout

Now that we know what the max idle timeout is, what about idle timeouts less than that? That is to say, before we hit the upper bound in idle timeout, what were the other idle timeout's that Lambda hit along the way?

There's a lot going on here but some observations:

- there is much less variance among bigger Lambdas - after 1792MB, most of the idling is done at the max idle timeout (which ranges from 26-54min)

- smaller Lambdas (under 1792MB) have a much higher variance when it comes to idle timeout lengths but tend to idle at high timeouts (~1h)

Takeaways

So takeaways from this experiment?

- Lambdas in us-west-2 have a consistent idle timeout of 26min for all lambda sizes

- Lambdas in us-east-1 have varying idle timeouts, ranging from 22min - 65min

- Lambdas in us-east-1 with smaller memory sizes (under 1536MB) have the highest upper idle timeouts

- idle timeout is different between different AWS regions and you should not assume that benchmarks done in one region stay consistent across regions

- any number that is not officially announced by AWS is subject to change

Finally,I would be remiss at this point not to add the disclaimer that these benchmarks were done to satisfy my own curiosity and you shouldn't base your production worloads off these results.

That being said, if you're curious to run through any of the above scenarios, you can find the source code to run this experiment on github

Some ideas for further tests:

- Idle timeout of Lambda using Lambda Layers

- Idle timeout of Lambda run at increasing concurrencies

- Idle timeout of Lambda in VPC

- Idle timeout of Lambda that make use of their scratch space

- Idle timeout of Lambda run during region peak hours (looking at you Netflix)

Hope you found this article useful and may the Lambda be (warm) with you!

Tags

Backlinks